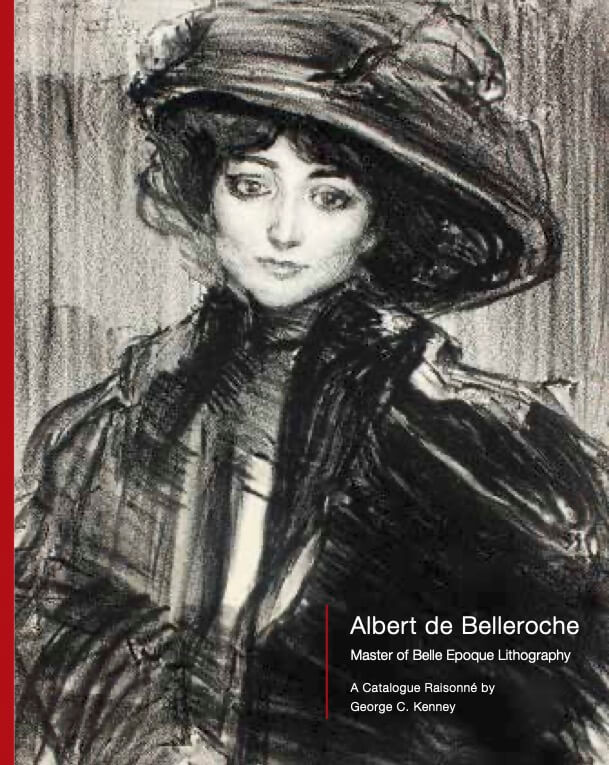

This Catalogue Raisonné is the culmination of 35 years of collecting, studying, and cataloging Albert de Belleroche’s nearly 1,000 lithographs, his career, and his life. I am profoundly thankful and express my deepest appreciation to the many people who have contributed their knowledge and expertise to this exciting journey and played a role in making this Catalogue Raisonné possible.

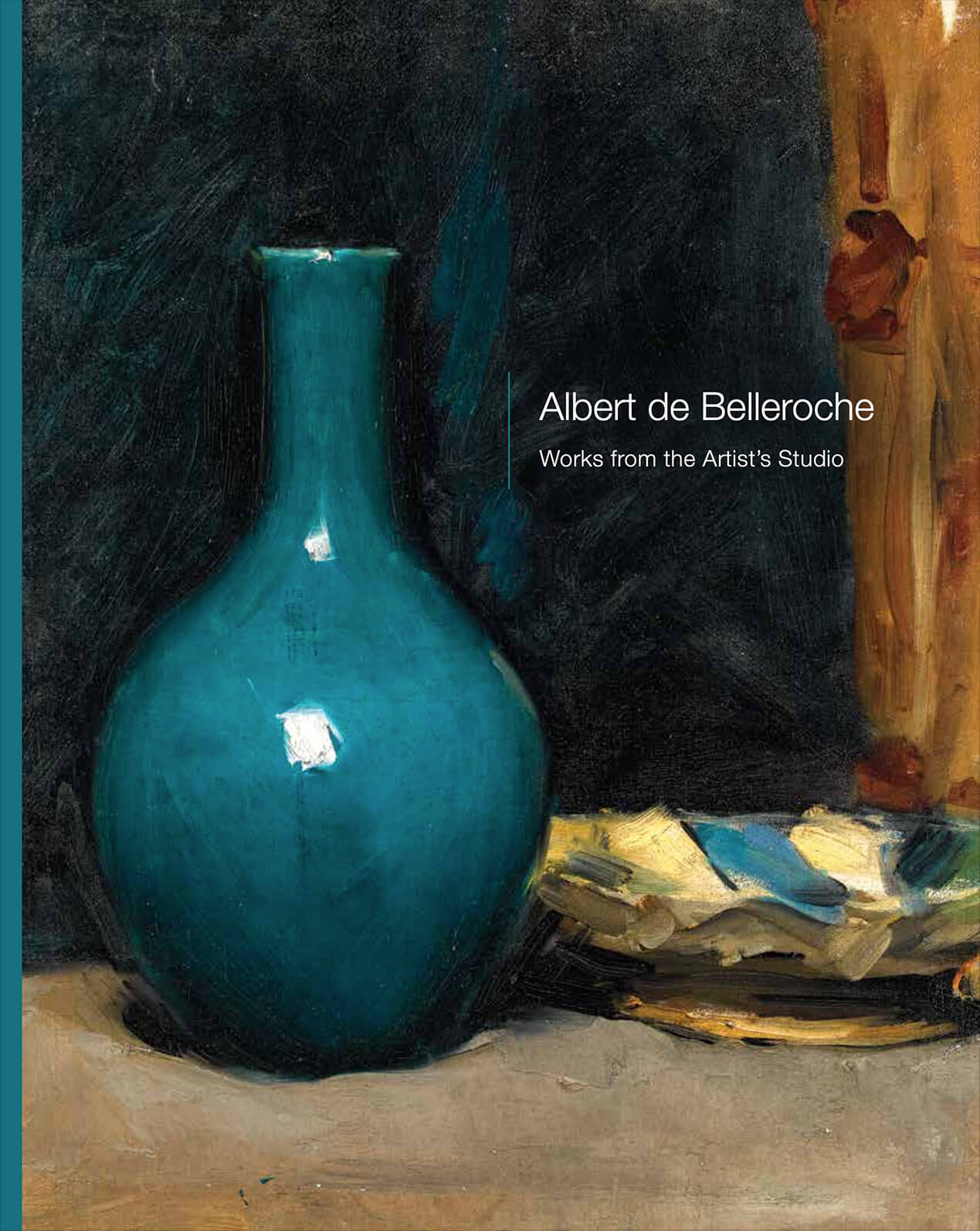

For their invaluable guidance, and provision of lithographs and photographs, I thank Theodore B. Donson, Marvel Griepp, Steven Kern, Richard Reed Armstrong, Paul Liss, Eva Liss, Bryan Smith, Sam Davidson, Rebecca McDonald and many others.

For access to Belleroche family private journals, letters, family stories, art and photographs, I am grateful to Gordon Snell. He sent me boxes of photos and unpublished Belleroche family materials containing first-hand accounts from Julie de Belleroche, Alice de Belleroche Sutton, William de Belleroche, and Gordon Anderson.

For assistance in the creation of the extensive image database and spreadsheet of over 1,000 lithographs, I thank Beidan Huang, Adam Stallings, Meghan Bach, Sylvia Gibson, Rachel Snigaroff, Jim George, Alex Acra, Lexie Zhang, Clara Zhao, Elizabeth Pieratt and many others who have contributed to this project over many years.

For their patience, support, and encouragement, I am grateful to my editor, David Maes and my publisher Paul Liss.

And finally, I express my deepest gratitude to my wife, Olga Kitsakos-Kenney, for her loving and enduring support over our 35-year journey with Albert de Belleroche.