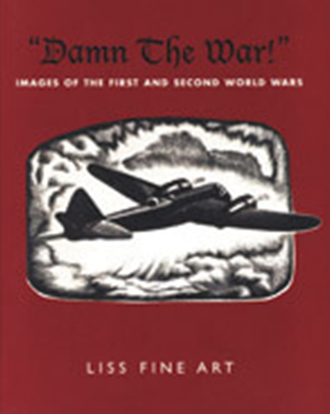

This catalogue presents a view of the First World War through a multifarious record of two and three dimensional works of art: paintings, drawings, prints, sculpture, reliefs, posters, postcards, photographs, silhouettes and ceramics appear in the following pages. The material has been grouped into 14 subsections under the general headings of Combat, The Home Front and The Aftermath. These groupings highlight the themes that inspired both the fine and popular arts, although some are looser in association than others, and none are mutually exclusive. The introduction gives a more general survey of the underlying factors that influenced or determined the visual responses to the First World War.†Although outside the remit of this catalogue, the accompanying exhibition includes other†wartime objects from the collection of David and Judith Cohen, including trench art, commemorative ware, sweetheart brooches, games, puzzles and miniatures.